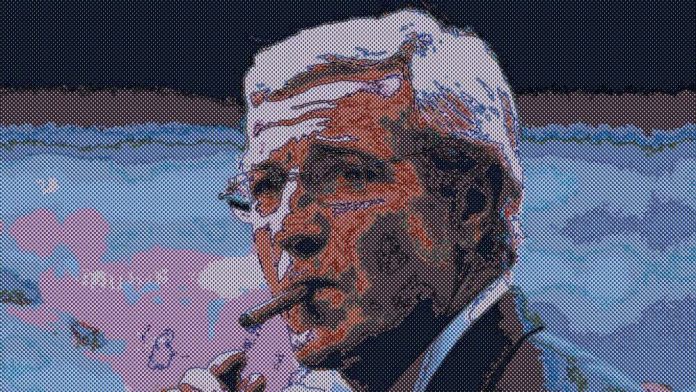

In the pantheon of football management, there is an exclusive club of men who have commanded the touchline with such terrifying serenity that they seemed to be playing a different game entirely. Sir Alex Ferguson, a titan in his own right, once described the experience of looking over at the opposing bench in Turin. He saw a man in a leather coat, smoking a small cigar, looking “smooth and calm” while Ferguson felt like a worker in a tracksuit being drowned in the pouring rain.

That man was Marcello Lippi. With his silver hair, piercing blue eyes, and a resemblance to Paul Newman that the Italian press never tired of pointing out, Lippi was the cinematic embodiment of the Mister. But behind the aesthetics lay a tactical pragmatist and a psychological engineer who dragged Italian football from the defensive dogmas of the past into the high-pressing modernity of the 21st century. He remains the only manager in history to have conquered both the UEFA Champions League and the FIFA World Cup.

This is the story of how a sweeper from Viareggio built the most feared club side of the 1990s and, amidst the ashes of a national scandal, orchestrated Italy’s fourth symphony in Berlin.

The Architect from the Coast

Born in Viareggio on the Tuscan coast in 1948, Lippi’s life was shaped by the sea. Before he was a tactician, he was a sweeper—a libero—spending the bulk of his playing career, from 1969 to 1979, organising the defence of Sampdoria. The sweeper’s role is cerebral by nature; it requires one to see the game as a whole, to anticipate disaster before it strikes. It was the perfect education for a future manager.

Lippi hung up his boots in 1982, the same year Italy won their third World Cup, and immediately moved to the dugout. His apprenticeship was long and unglamorous. He cut his teeth in the youth ranks of Sampdoria before embarking on a journeyman’s tour of Italy’s lower divisions—Pontedera, Siena, Pistoiese, and Carrarese. It wasn’t until 1989, at the age of 41, that he made his Serie A debut with Cesena.

But the turning point—the moment the world began to notice the smoke rising from the bench—came in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius. In 1993, Lippi took charge of Napoli. The club was in financial disarray, suffering a severe hangover from the Diego Maradona era. Yet, amidst the chaos, Lippi forged a unit. He took a young Fabio Cannavaro under his wing and guided a cash-strapped squad to UEFA Cup qualification. It was here that Lippi’s core philosophy crystallised: a group of average players functioning as a cohesive unit will always defeat a disjointed collection of superstars.

Vittorio Chiusano, the president of Juventus, watched Lippi’s Napoli hold his star-studded team to a draw and made a mental note. The Old Lady needed a new suitor, and the man from Viareggio was the chosen one.

Revolution in Black and White

When Lippi arrived at Juventus in the summer of 1994, the Turin giants were sleeping. They had not won the Scudetto since 1986, watching helplessly as AC Milan and an emerging Parma dominated the peninsula. The team Lippi inherited was defined by one man: Roberto Baggio, Il Divin Codino (The Divine Ponytail).

Lippi’s first act was a declaration of war on the status quo. He vowed to make Juventus less “Baggio-dependent”. It was a move of immense bravery; Baggio was the best player in the world, the reigning Ballon d’Or winner. But Lippi viewed reliance on individual genius as a structural weakness.

Fate intervened in November 1994 when Baggio suffered a knee injury against Padova. In his absence, Lippi unleashed a tactical revolution. He shifted to an aggressive 4-3-3, placing his trust in a devastating physical trident of Gianluca Vialli, Fabrizio Ravanelli, and a bushy-haired 20-year-old named Alessandro Del Piero.

The midfield, anchored by the iron-willed Antonio Conte and the tactical intelligence of Didier Deschamps and Paulo Sousa, became an engine room of “brains, heart, legs, and skill”. They pressed high, played with ferocious verticality, and overwhelmed opponents. In 1995, Lippi delivered the domestic double—the Scudetto and the Coppa Italia—in his debut season. The Baggio era was over; the Lippi era had begun.

The Kings of Europe

If 1995 was the domestic conquest, 1996 was the global coronation. Juventus marched to the Champions League final in Rome to face Louis van Gaal’s Ajax. Ajax were the defending champions, a total football machine that had dethroned Milan. Lippi, however, had spent months studying videotapes of the Dutch side, cigar in hand.

He recognised that Ajax’s rigid positioning could be disrupted by relentless man-marking and pressing in midfield. In the final, Juventus suffocated Ajax. Though the match ended 1-1, Juventus triumphed on penalties. Vladimir Jugović struck the winning spot-kick, and Marcello Lippi had restored the Old Lady to the summit of European football for the first time in 11 years. Later that year, they defeated River Plate to win the Intercontinental Cup, officially becoming the best team in the world.

Lippi’s genius lay in his unsentimental evolution. After winning the Champions League, he sold his captain, Vialli, and his top scorer, Ravanelli. In their place came a young Christian Vieri and a shy, lanky Frenchman from Bordeaux named Zinedine Zidane.

Initially, Zidane struggled with the brutal physicality of Italian training and tactics. But Lippi adapted. He shifted his system to accommodate the Frenchman, allowing Zidane to float behind the strikers. With Edgar Davids—”The Pitbull”—arriving in late 1997 to provide the midfield growl to Zidane’s grace, Juventus reached two more consecutive Champions League finals in 1997 and 1998, though they lost both to Borussia Dortmund and Real Madrid respectively. Domestically, however, they remained untouchable, winning Serie A titles in 1997 and 1998.

The Inter Nightmare and the Baggio Feud

In 1999, Lippi made the controversial move to Inter Milan. It was a disaster defined by a toxic collision of egos. Lippi reunited with Roberto Baggio, but the relationship had curdled into open hostility.

In his autobiography, Baggio accused Lippi of asking him to be a “spy” in the dressing room to report on players speaking against the manager. Baggio refused. “I refused and became the substitute of substitutes,” Baggio wrote. “He started a war with me at Inter”. Lippi denied the “mole” allegation, claiming he only treated Baggio like any other player based on fitness.

The tension culminated in a Champions League playoff against Parma in 2000. Lippi’s job was on the line. In a twist of irony, Baggio produced a masterclass, scoring two stunning goals to win the match 3-1 and save Lippi’s job. Despite the victory, the fracture was irreparable. Baggio left for Brescia, and Lippi was sacked just one game into the following season after a defeat to Reggina.

Lippi returned to Juventus in 2001, proving that the Inter spell was a blip. He sold Zidane for a world-record fee and used the money to build a new spine: Gianluigi Buffon, Lilian Thuram, and Pavel Nedvěd. The result? Two more Scudetti and another Champions League final in 2003, which Juve lost on penalties to Milan.

The Berlin Masterpiece

In July 2004, Marcello Lippi answered his country’s call. The Azzurri were broken, reeling from a disastrous Euro 2004 and the Trapattoni era. Lippi’s mission was to make the country fall in love with the national team again.

The road to the 2006 World Cup in Germany was paved with chaos. In May 2006, just weeks before the tournament, the Calciopoli match-fixing scandal erupted, implicating Juventus and several top Italian clubs. The Italian media called for heads to roll. Lippi, given his Juventus history, was under immense pressure to resign.

Then, tragedy struck. Former Juventus player Gianluca Pessotto attempted suicide, devastating the large contingent of Juve players in the Italy squad, including captain Fabio Cannavaro.

Lippi used the chaos as fuel. He encircled the wagons, creating a “siege mentality.” He told his players to transform the external negativity into positive energy. He forged a group that was psychologically bulletproof. “To this day I am not convinced of having brought together… the technically best players,” Lippi later admitted. “But I was firmly convinced I called the ones that could create a team”.

The Tactical Canvas

On the pitch, Lippi displayed immense tactical flexibility. He built a system that allowed two playmakers, Francesco Totti and Andrea Pirlo, to coexist. Totti operated in the hole, while Pirlo dictated play from deep, protected by the snarling Gennaro Gattuso and the tireless Simone Perrotta.

Defensively, Italy were imperious. Anchored by Cannavaro—who Lippi called “the strongest defender in the world”—and Gianluigi Buffon, the Azzurri conceded only two goals in the entire tournament: an own goal against the USA and a penalty in the final.

But Lippi was no defensive ideologue. In the semi-final against host nation Germany, with the game deadlocked deep in extra time, Lippi gambled. Rather than settle for penalties, he threw on four attacking players: Totti, Del Piero, Vincenzo Iaquinta, and Alberto Gilardino. It was a moment of tactical audacity that stunned the Germans. “I said to myself, ‘Let’s put on four attackers and go for it’,” Lippi recalled.

It worked. Fabio Grosso curled in a 119th-minute winner, and Del Piero sealed it moments later.

The Final Act

The final against France in Berlin was a war of attrition. Zinedine Zidane, Lippi’s former pupil, scored an early penalty, but Marco Materazzi equalised. The game is remembered for Zidane’s shocking headbutt on Materazzi in extra time, a moment that left Lippi “stunned” on the touchline.

It went to penalties. Italy, a nation haunted by penalty shootout failures in 1990, 1994, and 1998, did not miss. Lippi had chosen Fabio Grosso, the hero of the semi-final and a player from Palermo, to take the decisive fifth kick because he was “the last-minute man”. Grosso scored.

Lippi had done the impossible. He had taken a team on the brink of a nervous breakdown amidst a national scandal and turned them into world champions. He described it as his “most satisfying moment as a coach,” surpassing even his triumphs with Juventus.

The Legacy

Lippi stepped down three days after the World Cup final. Although he returned for a disappointing spell in 2008 and later found success in China with Guangzhou Evergrande (winning the AFC Champions League to complete a unique continental double), his legend was cemented in Berlin.

His influence permeates modern football. A staggering number of his 2006 squad—Cannavaro, Gattuso, Pirlo, Oddo, Grosso, Inzaghi, De Rossi, Nesta, Gilardino—have become coaches, citing Lippi’s management of the “human side” of the game as their inspiration. He taught them that tactics are essential, but the unity of the group is absolute.

Marcello Lippi was the man who stared into the eyes of legends like Ferguson and Zidane and never blinked. He was the man who smoked a cigar in the rain while others drowned, secure in the knowledge that he had built not just a team, but a family. As he once said: “When we weren’t the strongest, we were the best”.