The Felt on Red Square

On a warm July day in 1936, the cobblestones of Red Square were concealed beneath a massive, green felt carpet. In the shadow of the Kremlin walls and the kaleidoscopic domes of St. Basil’s Cathedral, two teams from the Spartak sports society prepared to play a football match. This was not a standard fixture, but a carefully choreographed exhibition designed for an audience of one: Joseph Stalin. Nikolai Starostin, the founder of Spartak, had arranged the spectacle to convince the Soviet leader that football was a valid pursuit for the proletariat. The match was theatrical; the goals were pre-planned to ensure the action remained engaging, and tackles were softened to prevent injury in front of the Politburo.

When the final whistle blew, the General Secretary waved a white handkerchief, signalling his approval. It was a moment of surreal synthesis between the spontaneous joy of sport and the rigid choreography of totalitarianism. Edelman described the game as a spectacular challenge to the usual displays of order and discipline that characterised Soviet parades, introducing a regulated form of chaos into the heart of the capital. Serious Fun: A History of Spectator Sports in the USSR (Cambridge University Press). Football had officially survived its ideological infancy, but it had also entered a pact with the state that would define its existence for the next five decades.

The Ideological Battlefield

To understand why a felt carpet on Red Square mattered, one must understand the perilous position of sport in the years following the 1917 Revolution. The Bolsheviks viewed organised sports with deep suspicion. The new regime debated whether competitive athletics were a bourgeois relic, a tool used by capitalists to distract the working class and foster unhealthy divisions. Two primary factions emerged in the 1920s to contest the soul of the Soviet body: the “hygienists” and the “Proletkult” movement.

The hygienists, largely composed of doctors and medical professionals, argued that the pursuit of records—running faster or kicking harder—was a pathology that led to physical exhaustion and “excitement,” states incompatible with the rational Soviet worker. They advocated instead for fizkultura (physical culture), a non-competitive system of callisthenics and gymnastics designed to optimise the body for labour and defence without the tribalism of team sports.

The Proletkult movement was even more radical. They sought to replace matches with theatrical displays of cooperation, utilising games with names like “Rescue from the Imperialists” or “Smuggling Revolutionary Literature Across the Frontier”. In their view, the spectator was a passive entity, and the goal of sport should be collective participation rather than the observation of elite performance.

However, the “need to play,” as Leon Trotsky noted, asserted itself against theoretical purity. By the mid-1920s, the state pragmatically pivoted from prohibition to institutionalisation. If football could not be abolished, it would be harnessed. The resulting structure tethered clubs to specific arms of the Soviet apparatus, creating identities that persisted until the union’s collapse. The Red Army founded CDKA (later CSKA); the trade unions backed Spartak; the automotive industry supported Torpedo; and the railways organised Lokomotiv. Most ominously, the secret police—the NKVD—established Dynamo, an organisation intended to project internal security and discipline. This decision to integrate football into the state machinery ensured that the sport would never be merely a game; it would be a proxy for the internal friction of the Soviet superpower.

The Architect and the Policeman

The bureaucratic colonisation of sport set the stage for one of the most intense personal rivalries in the history of the game, one that transcended points in a league table. Nikolai Starostin, the charismatic captain and organiser of Spartak Moscow, found himself in a dangerous orbit with Lavrentiy Beria, the head of the NKVD and patron of Dynamo Moscow. Spartak, funded by independent trade co-operatives (Promkooperatsiia), was the “people’s team,” a rare entity that felt distinct from the state’s hard power.

The animosity was personal. Starostin had once humiliated Beria on the pitch during the latter’s days as a crude amateur player in Georgia, a slight the police chief never forgave. In the late 1930s, as the Great Terror consumed the Soviet political elite, the football pitch became a dangerous stage. Spartak won the league and cup double in 1938 and 1939, challenging the dominance of the government-run clubs.

The vendetta manifested in surreal interventions. In 1939, Spartak defeated Dynamo Tbilisi in a cup semi-final and went on to win the final. Beria, incensed by the loss of his favoured Georgian side, used his political weight to order a replay of the semi-final weeks after the tournament had concluded. Spartak won the replay as well, a public defiance of the secret police that was as dangerous as it was triumphant. Starostin later recalled looking up at the dignitaries’ box and seeing Beria throwing chairs in uncontrollable rage.

By 1942, with the war against Germany raging, Beria made his move. The Starostin brothers—Nikolai, Andrei, Petr, and Aleksandr—were arrested and interrogated at the Lubyanka. They were initially accused of plotting to kill Stalin, a charge so absurd it was eventually dropped, only to be replaced by charges of praising bourgeois sport and “instilling the mores of the capitalist world into Soviet sport”. They were sentenced to ten years in the Gulag. Yet, even in the labour camps, football offered a shield; camp commandants, eager to win local championships, recruited Nikolai to coach their teams, valuing his tactical mind over his status as a political prisoner.

The War and the World Stage

While the Starostins suffered in the camps, the Second World War created a new, tragic mythology in Ukraine. Following the Nazi invasion in 1941, Kyiv fell under German occupation. A group of former professional players, primarily from Dynamo Kyiv and Lokomotiv, found work at a bakery to survive the occupation and formed a team known as FC Start. Throughout the summer of 1942, they played a series of matches against garrison teams comprising Hungarian, Romanian, and German soldiers, winning them all comfortably.

On August 9, 1942, FC Start faced Flakelf, a team assembled from Luftwaffe anti-aircraft personnel. This encounter would be immortalised by Soviet propaganda as the “Death Match.” The official narrative, cultivated in the post-war years, claimed that the Ukrainian players were visited by an SS officer before kickoff and ordered to lose or face execution. According to the myth, they refused to give the Nazi salute, won the game 5–3, and were executed in their kits immediately after the final whistle as martyrs for the communist cause.

Historical inquiry following the dissolution of the USSR revealed a reality that was both less cinematic and more complex. The match was played hard, but eyewitnesses and photographs confirm a relatively relaxed atmosphere post-match, with players from both sides mingling. The tragedy came later. Nine days after the victory, players were arrested, likely due to the Gestapo suspecting them of being NKVD agents rather than because of the football result. Nikolai Korotkykh died under torture, and three others—Ivan Kuzmenko, Oleksiy Klymenko, and goalkeeper Nikolai Trusevich—were executed at the Syrets concentration camp months later, victims of the brutal occupation machinery rather than a single sporting result.

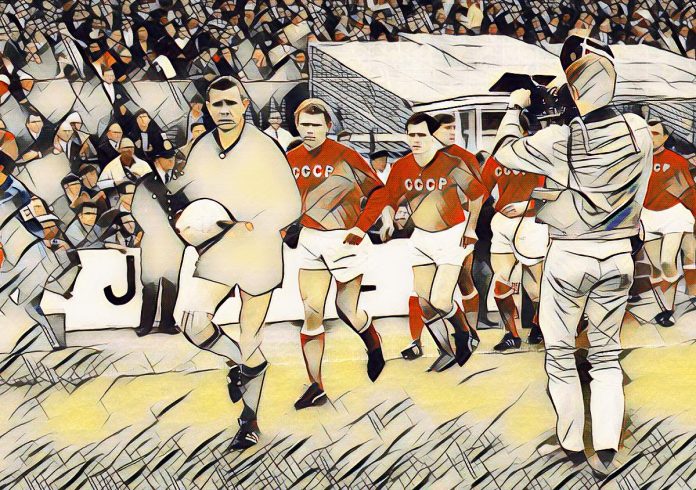

As the war ended, the Soviet Union sought to re-enter the global community, using sport as a soft-power wedge. In November 1945, Dynamo Moscow toured Great Britain, an event that carried immense diplomatic weight. The British press, expecting a team of factory workers and amateurs, treated the visitors with a mix of curiosity and condescension, dubbing them “The Silent Ones”.

When Dynamo stepped onto the pitch at Stamford Bridge to face Chelsea, the scepticism evaporated. They played a style of football that was alien to the British game: fluid, interchangeable, and grounded in “pass and move” collectivism rather than individual dribbling. This movement, which confused the rigid British defenders, was later termed “Organised Disorder”. They drew 3-3 with Chelsea, demolished Cardiff City 10-1, and defeated a strengthened Arsenal side 4-3 in a match obscured by heavy London fog. The tour concluded with a 2-2 draw against Rangers in Glasgow. The “mysterious Muscovites” returned home unbeaten, having shattered the illusion of British footballing superiority and establishing the USSR as a serious athletic power.

The Scientific Revolution

If the post-war era established Soviet football as a force of nature, the 1970s transformed it into a science. The locus of power shifted south, away from Moscow and toward Kyiv, driven by Valeriy Lobanovskyi, a man who viewed football less as a game and more as a solvable engineering problem. A former winger with a degree in thermal engineering, Lobanovskyi teamed up with statistician Anatoly Zelentsov to create a cybernetic approach to the sport.

Working out of Dynamo Kyiv, Lobanovskyi and Zelentsov treated the pitch as a laboratory. They rejected the idea of the individual star, arguing that “the efficiency of the subsystem is greater than the sum of the efficiencies of its individual elements”. They developed a pressing system that required players to be universally capable—attackers had to defend, and defenders had to attack. To achieve this, the physical conditioning was brutal. Players underwent “lactate threshold training,” pushing their pulse rates above 200 beats per minute to ensure they could sustain high-intensity pressing for ninety minutes.

The “Zelentsov Centre” at Dynamo Kyiv utilised early computer analysis to track “coalition actions” and pass completion rates, developing the “18% rule”—a governing algorithm which posited that a team would not lose a match if their error rate in key moments did not exceed that specific threshold. This was a precursor to modern data analytics, operating on punch cards and magnetic tape behind the Iron Curtain.

Lobanovskyi’s methodology produced results that stunned Europe. Dynamo Kyiv won the Cup Winners’ Cup in 1975, defeating Ferencváros 3-0, and then defeated the mighty Bayern Munich in the Super Cup, suffocating the German giants with a relentless press. The team won the Cup Winners’ Cup again in 1986, playing a brand of football that the Spanish press described as being “from another planet”. This scientific approach reached its zenith with the national team at Euro 1988. The squad, largely composed of Dynamo Kyiv players, defeated Italy in the semi-finals with a display of suffocating intensity before falling to the Netherlands in the final. Lobanovskyi’s legacy, the “system,” would go on to influence modern tactical thinkers like Ralf Rangnick and Arrigo Sacchi, proving that the Soviet approach had unlocked fundamental truths about space and pressing.

The Unraveling

While Lobanovskyi perfected the machine in Ukraine, the southern republics used football to express flair and distinct national identities that chafed against Soviet homogeneity. In 1973, Ararat Yerevan achieved a historic double, winning the Soviet Top League and the Cup. For Armenians, the victory was a surge of national pride, a “safety valve” for nationalist sentiment that allowed them to celebrate their unique heritage within the Soviet framework. The team played with an improvisational technical skill that contrasted with the scientific rigour of Kyiv. Similarly, Dinamo Tbilisi in Georgia became renowned for a style of play characterised by immense speed and technical beauty, winning the Cup Winners’ Cup in 1981 by defeating Carl Zeiss Jena. These successes from the periphery demonstrated that while the Soviet state could control the league structure, it could not homogenise the cultural expression of the game.

Beneath the surface of international trophies and scientific advancements, however, the domestic game struggled with grim realities. The stadiums were sites of friction between the state and an increasingly alienated youth culture. By the late 1970s and 80s, an organised fan movement (fanatskoe dvizhenie) emerged, particularly around Spartak Moscow, challenging the passive role assigned to spectators by the state. This tension culminated in tragedy on October 20, 1982, at the Lenin Stadium in Moscow. During a UEFA Cup match between Spartak and Haarlem, a crush occurred on an icy staircase. The official death toll was 67, though independent estimates suggested it was significantly higher. The disaster was exacerbated by militia mismanagement and was subsequently covered up by the authorities for years, a dark secret shared by those who survived the crush.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s brought a rapid and chaotic end to the “Red Machine.” Mikhail Gorbachev’s reforms of perestroika allowed players to move abroad for the first time, leading to an exodus of talent to Western Europe. Stars like Oleksandr Zavarov and Rinat Dasayev left for Italy and Spain, weakening the domestic league. As political control waned, the league began to fracture along national lines. Georgian clubs withdrew in early 1990, followed by Lithuanian teams, dismantling the unified competition before the USSR itself officially ceased to exist.

The Legacy of the Machine

The final Soviet Top League season in 1991 was won by CSKA Moscow, breaking the long dominance of Kyiv and Spartak, but it was a victory in a dying house. The national team played its final match in November 1991, and a temporary “Commonwealth of Independent States” team competed at Euro 1992, a ghostly coda to a once-mighty sporting empire.

The legacy of Soviet football is found not just in the trophy cabinets of Moscow, Kyiv, and Tbilisi, but in the evolution of the global game. The innovations of Lev Yashin redefined the role of the goalkeeper from a passive shot-stopper to an active sweeper-keeper. The cybernetic theories of Valeriy Lobanovskyi laid the groundwork for modern data analytics and high-pressing systems employed by the likes of Jürgen Klopp and Pep Guardiola.

The system demanded total control yet produced moments of uncontrollable brilliance. It was a paradox of repression and creativity, where a match on Red Square could charm a dictator, and a match in a bakery could inspire a nation. In the centre of Kyiv, near the Dynamo stadium, sits a bronze statue of Lobanovskyi. He is depicted sitting on a bench, body hunched in perpetual tension. The inscription on his tombstone reads, “We are alive as long as we are remembered”. In the pressing structures of the modern Champions League and the tactical spreadsheets of analysts worldwide, the machine he built is still running.

Part of the Soviet Football Series

This article forms part of an ongoing long-form series exploring the history, ideas, and legacy of Soviet football — from the rise of Dynamo Kyiv and the work of Valeriy Lobanovskyi to the collapse of the Soviet system and its quiet influence on the modern game.

You can begin the full series here:

→ Soviet Football: History, Dynamo Kyiv, Lobanovskyi, and Legacy

Or continue reading through the project:

- Before the System — Football in the early Soviet decades

- Dynamo Kyiv and the Making of Power

- Valeriy Lobanovskyi and the Cybernetic Game

- 1975: Proof of Concept

- 1986: The Atomic Team

- Euro 1988 and the Last Great Machine

- Exile, Fragmentation, and the 1990s

- Legacy in the Modern Game

Read together, these essays trace how a vanished football culture continues to shape the sport that followed.